A Short Story by Parthapriyo Basu

- Posted on March - 22 - 2025

- By

Bhaiphonta

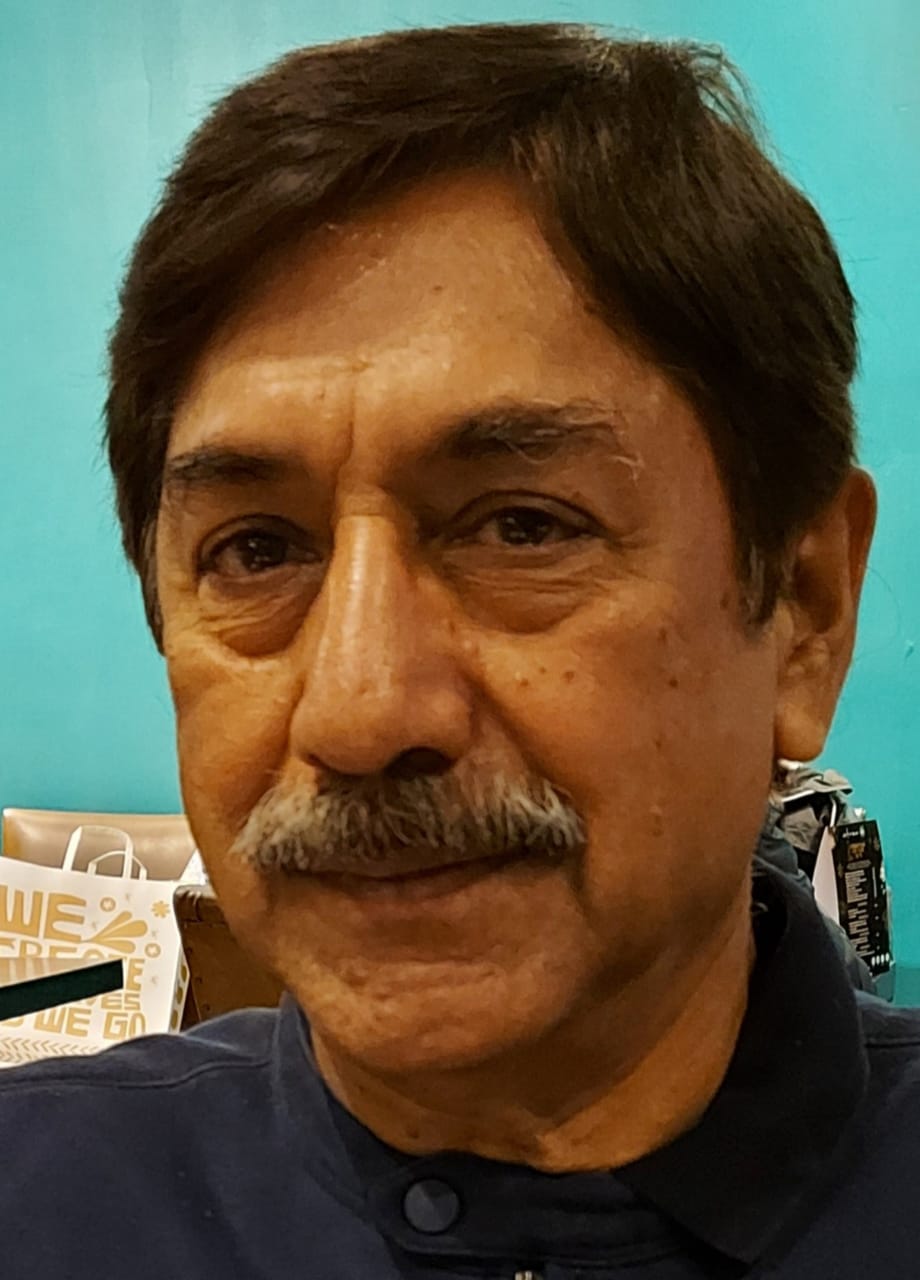

ParthapriyoBasu

Bengali families usually pass through so many rituals. It may be social, religious, or even regional which is practised among the people of a particular region only. Ranjan cannot say that he likes those year-round festivities and rituals much. To him, these are often bothersome. Usually, he never becomes a part of it, unless he is compelled to. But at the same time, he enjoys a few social rituals particularly which bring people together. Loneliness is something he nourishes only when his creative impulse is awakened. He has correctly noted that even writing a four-line poem is not easy if a few family members are present around him. Sometimes when he is in a large medley of people and his creative inspiration rises suddenly, he makes himself solitary inside his mind. Then he becomes another he within himself. This practice has not been easy. He must concentrate a lot. Diversion comes more often than concentration. He wipes it out and makes a clean path through the foggy atmosphere within himself. His mind could concentrate only along that narrow strip of a path. This practice has made him absent-minded to some extent, but he does not mind. To him creative pursuit is the other name of life, and of course a better life. Ranjan cannot say how such impulses appear in his mind. He has heard that some discharge occurs in the brain at the time of such rising impulses. He is not sure.

After the age of so-calledmaturity, he realized that his world was gradually being separated from common social life. Not that he does not subscribe to the goodness of usual social livelihood, rather he has some respect for common people and their common social life. He understands that living an ordinary and common social life abiding by all the social rules and customs is difficult. Rather it is easier to be a social outcaste.

The great Durga puja of the Bengali community does not mean much to him, though he knows well that a huge turn over occurs in the business world during this Bengali festival. He feels no inspiration towards pandal hopping or even visiting at least one or two famous puja mandaps. Surprisingly, Bijaya Dashami being a ritual of togetherness and exchange of love and respect is liked by him. Some of the family members ask him,even not liking the puja festival at all, why heparticipates in the ritualof Bijaya Dashami?Maybe he does not write Durga naam anymore, but bowing his head before the elders and touching their feet is of course liked by him in all spirits. This way a deep-rooted course of tradition and a very strong impulsiveness towards breaking the tradition for his own liking has germinated a seed of self-controversy within himself. The sapling has grown up. Now it is a tree which sways emotionally during the strong breezes of social incidences.

Alike Bijaya Dashami he also follows the ritual of Bhratridwitiya or Bhaiphonta. Usually, he visits his cousin-sister during the day of ceremony. This year on Pratipad, that is the day before Bhratridwitiya, suddenly his mind waslifted from the page of the novel he was going through. The entire page turns blurred. He could not decipher a single word out of it. The dark street-lightless path of asphalted Kulpi Road appeared before his eyes. A beam of light penetrated through the darkness. The light was bumping up and down depending on the condition of the road. It was the light of a Calcutta taxi during theearly 60s of the last Century. The colour of the taxi was still a combination of black and yellow. Inside the cab three girls and two boys were chatting between themselves in a low voice. In the front seat, beside the cab driver sat one middle-aged hefty person with dhuti and panjabi on. The sleeves of the panjabiwere crinkled with expertise. He was a famous stage actor and drama-director. Three girls are his daughters. And one of the boys is his son. The other boy is their cousin, their chhotomama’s son. The occasion is the purchase of new garments from Gariahat before Durga Puja. After the shopping while they were returning to the small town of South 24 Parganas where the gentleman resided. The other boy would stay for the night and would return home on next morning with his Pisemoshai. That journey was also highly entertaining for the little boy as the gentleman used to travel in first class in those old coal-burning locomotives. The compartment of the train would remain almost vacant except for two of them and two others more.

After a few weeks there would be the ceremony of bhaiphonta when the little boy’s cousin sister and cousin brother would visit their house in south Calcutta with their mother. The ceremony would be held in their house. The whole month from Mahalaya to Kali puja and bhaiphonta was a time of joy, time of delightfulness and hope. Every year Ranjan experienced something new which made him a little more advanced in the journey of life.

Ranjan shifted his concentration from the cinematic past to the real present. But was thepresent a real present? Within moments the present becomes past. He wants to get hold of the present, but every moment it slips through his hand and vanishes into the eternal past. The childhood days have been changed in all dimensions and feelings. Can Ranjan forget those days when one of his elderly sisters used to comb his hair during the afternoon before they all went out to the courtyard to play? That holding of bhaiphonta ceremony continued up to the adolescence. Then there was a gap, a long gap when it became irregular to some extent. It further resumed after Ranjan became a real adult who followed his own likings, and he made it a norm to visit his cousin sister in-law’s houses during the ceremony of bhratridwitiya.

Contemplating about the past it suddenly appeared in his mind that of the four cousins Shuvoda and didi are no more in this mortal world. Only two of their sistersstill wait for Ranjan and his brother Sujan every year on the day of bhaiphonta. The faces of the departed cousins very faintly floated in the air in front of Ranjan’s eyes. He came back to senses. Had he purchased the gifts for his sisters? Well, he would have to purchase it. Suddenly, he thought of mejdi. As far as he could remember she does not live in her in-law’s house anymore. After the demise of her husband, she had to shift elsewhere with her married son’s family because their house turned dilapidated. Her son is a sober person and dutiful too. She must be living with them. He searched through his phone for the number of his nephew. No, it is not there. Well, he has a niece too. Yes, her phone number is perhaps stored in his phone. He searched through the list again. Yes, it’s there.

He called his niece, ‘where does mejdi live now? Do you know that?’

‘Why not? Every day I meet ma on my way to school where I teach.’

‘She is not with your brother anymore?’

‘No, you must know that she has had vertigo in recent years. She has fallen number of times. One of those turned fatal. She had three stitches on head.’

‘What about your brother and his wife?’

‘No, no, they are not to be blamed. You know that dada does not earn much and with that they cannot meet their hand to mouth comfortably. On the other hand, their son studies in class nine of a reputed English medium school. So, they must spend a lot towardsthe education of their son. Obviously, no question arises about changing the school. So, boudi had to start a small business selling ladies garments on her own. She goes out of the house at least for a few hours each day.’

‘So, does mejdi stay alone?’

‘Not that exactly, an aya stayed in the house to look after her. Perhaps she was in the bathroom when ma had fallen on the threshold of a room while going to have some drinking water. The incident occurred at that moment.’

‘Where is she now? In a hospital or a nursing home?’

‘No, no, not in a hospital or nursing home. I have arranged one care home under the supervision of a senior doctor for her. The home is located on the way to my school. This year if you are interested to visit her on the day of bhaiphonta I will give you the address of the home. You know, mother gets her widow pension, and the expenses are almost met through that.’

‘Is it so? Nice. Can mejdi take it?’

‘I don’t think she doesn’t realise the changing situation.’

‘Good. Are you coming to the Home on that day dear?’

‘No, I am sorry. I visit her almost every day, but that day I should spend with my dada and my cousin brothers. You know what I mean.’

‘Yes, I do. Okay, then send me the address of the Home, so that I can meet her on that day.’

Ranjan’s niece Sunipasent him the address of the Home. Moreover, when Ranjan asked her if like other years if he would give her a sharee as a gift, would it be okay? Sunipa protested.

‘No use of Sharees to ma anymore, what she would require now is a maxi, and an Ensure for diabetics. But this Pujo I have gifted her number of suitable garments. You better stick to that diabetic food.’

Ranjan could not swallow it, but he understood the reality. He thought, this is here he can understand the present.

After having lunch at chhotdi’s home, in the late afternoon, Ranjan checked the address of the Care Home through his mobile phone and proceeded at a moderate speed towards the road on which the Home was situated. On his way Sunipa called him on the phone,

‘Mama, are you visiting mother today surely? I have already told her that you are coming. She is longing for you.’

‘Don’t worry, I’m going in that direction.’

‘You saved me mama, thank you.’

‘You don’t have to thank me, she’s my didi, hope you realise my feeling when I meet her in a care home on this day.’

‘I fully understand mama,but you know, it is troublesome for me to bring her to my in-law’s house, moreover, you also know, I’m a working girl too. Because I earn, I can spend money on my ailing and homeless mother.’

Ranjan did not speak a single word in reply. Slowly, he disconnected the Bluetooth.

Mejdi was ready to welcome her brother Ranjan sitting on a plastic chair, as she already knew that Sujan was ill and would not come.The brother and sister met with smiles that spoke of the lifelong relation between the two. Ranjan could understand that mejdi was maintaining good relationship with her roommates too. She had adjusted herself with the present condition. No repentance, no blaming, no emotional outburst. She praised her daughter in law more, mentioning less about her daughter Sunipa. Ranjan smiled within himself. Then handed over the gift, Ensure diabetic. They both smiled again. Ranjan touched the feet of his Mejdi.

Mejdi said, ‘You know Ranju, I don’t have any arrangements here, but you’ll not miss the Phonta.’

The little finger of Mejdi’s left hand slowly touched the central part of Ranjan’s forehead between the eyebrows without any curd or sandalwood solution. Mejdi closed her eyes in that position for a few minutes and Ranjan could hear the space of the Care Home’s Room number 12 was enchanting:

Bhaiyerkopaledilamphonta

Jomerdwareyporlokanta

JamunadaiJomkephonta

Jomjemniamar

Amar bhaitemniamar.

Perhaps, somewhere a conch was blown too, and he could feel the light heat coming from a flickering flame of a Pradip. On his way back he kept the coffee pack Mejdi had given him as a gift, on the passenger seat. This was the best Bhaiphonta of his life.

0 Responses